Over the holidays, Facebook took another misstep in its quest to get to know us. You may have woken up one morning to see its suggested “Year In Review” right at the top of your News Feed. The slideshow of images from our lives in 2014 came from the most engaged posts—the ones that got the most shares, likes, even impressions. So Facebook deduced that the most important parts of our lives equal the best parts of our life… which, of course, led to utter turmoil.

The most poignant example of how using an algorithm to interpret feelings of best and worst moments is from web designer and writer Eric Meyer. Meyer woke up to the cover of his year-in-review showing his smiling 6-year-old daughter, who he had tragically lost earlier this year. A life-changing event—thanks for pointing that out, Facebook—and the most devastating event in this man’s life.

As NPR reported, Meyer opened a blog post entitled “Inadvertent Algorithmic Cruelty” with this:

I didn’t go looking for grief this afternoon, but it found me anyway, and I have designers and programmers to thank for it. In this case, the designers and programmers are somewhere at Facebook.

There have also been far more unhappy campers:

So my (beloved!) ex-boyfriend’s apartment caught fire this year, which was very sad, but Facebook made it worth it. pic.twitter.com/AvU8ifazXa

— Julieanne Smolinski (@BoobsRadley) December 29, 2014

Which brings us to the bottom line: Facebook developers are trying to get to know us, using algorithms and stats and impression counts, and without asking our permission. But they’re missing the biggest point: we’re humans. Our lives are very complex. And oh yeah… we have this little thing called feelings.

Facebook developers: ping me when you can gauge my level of anxiety every time I get tagged in a photo. Ping me when you can measure whether that baby picture someone posted wasn’t a baby who’s having trouble being the normal size and weight. Ping me when you can sell my emotional responses to advertisers. But don’t try to tell me you know me from the amounts of likes and shares my photos got this year.

There’s an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, “The Measure of a Man,” where they go to court to decide whether Data, the android, is a machine that has learned how to be human, or whether he’s just a machine that they can take apart and put back together. They eventually realize that he’s learned how to love, and that he’s become emotionally attached to certain crew members. Certain items he cherishes, not for any practical reason, but because they have a sentimental meaning to him.

There’s an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, “The Measure of a Man,” where they go to court to decide whether Data, the android, is a machine that has learned how to be human, or whether he’s just a machine that they can take apart and put back together. They eventually realize that he’s learned how to love, and that he’s become emotionally attached to certain crew members. Certain items he cherishes, not for any practical reason, but because they have a sentimental meaning to him.

That kind of sentimental attachment is immeasurable; you know, that inexplicable thing that makes your cat pillow mean so much to you. It’s these complexities and nuances that make us human. And these complexities cannot be measured by anyone, period, so also not by Facebook. (Disclaimer: Data is an Android, so yes, a machine that has become human, but in the year 2364. A machine has also passed the Turing Test this year, but that’s only thinking, not feeling. The difference is that Facebook is a social networking site that’s trying to use our posts on social media to get to know us as humans, very different.)

When I came home for the holidays, my mom said, “Lauren, I know you don’t like vegetables.” She’s basically Facebook in this case. Because for 15 years that probably was the case. She analyzed the data. Well, in the past eight years I’ve become some sort of veggie-loving freak who drinks kale-and-beet smoothies every morning. Humans change, and it’s really unpredictable. We can’t even fully understand what someone is really saying behind what they are actually saying to us. Humans are constantly evolving, we’re very complex, and an algorithm will never capture that.

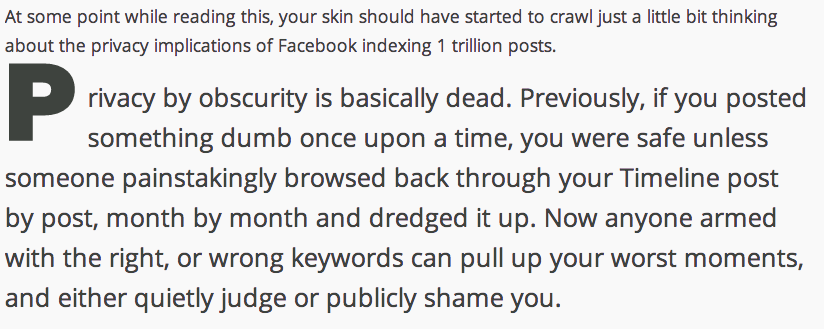

You’d think Facebook might try being a little more careful with things like this, considering the new “keyword post search,” a new Graph Search mechanism they just rolled out has a lot to do with this idea. Keyword Graph Search works like this: you can use the Facebook search bar to search through your posts of Christmas Past using keywords. For example, I could type into my search bar, “Lauren David dancing” and Facebook would bring up related posts with the words I searched for highlighted in yellow (blue on mobile.)

The results are ranked with a “personalization algorithm” that “combines the prevalence of keywords with a News Feed-style ranking based on how close you are with the author and loads of other signals” (explained in this breakdown of how to use it).

As Techcrunch so awesomely reflected, this feature is so much more than us now being able to look back on our own past posts and those of people we may or may not be stalking.

This is Facebook again trying to get to know us… but on a deeper level. Instead of just seeing our profile and interest data in the present time, they can see what and how we search through an index of trillions of our past posts for keywords, see our trends and progressions up to our current posts, and position targeted ads right under posts.

Facebook keyword advertising could change that. Instead of the related ads showing up on search results, they’d appear on your feed right after you post. All those ‘What movie should I see?’, ‘Can’t wait to visit Portland tomorrow!’, ‘My car just died’ posts are ripe with purchase-intent advertisers would love to exploit leverage. – via Techcrunch

You may say, well, Google’s been doing this forever, handing our searches to advertisers for billions of dollars. The difference, again, is that Facebook gets really personal. Plus, we’ve only recently started worrying more about privacy settings, or making photos only visible to our friends. Now that people can search back to our posts from years before we became more wary…. well, good luck. It’s like a treasure trove of embarrassing stuff we really didn’t want resurfaced. Posts that used to be a lot more time-consuming to find. Those are the initial implications of the keyword post search. Techcrunch was also on point with this:

But what if we think beyond even advertising? You get into an argument with your friend over what you were wearing to that New Year’s party in 2011. Now she can just search and bring up the old post and prove you wrong. Who did your fiance hang out with for his birthday three years ago? Search until you find the post, and feel like shit.

There’s a show on BBC called Black Mirror, it’s brilliant, about the not-so-distant future of technology. It’s terrifying, and all of this Facebook news reminds me of two episodes. In the first, a girl’s boyfriend dies. She, of course, has so many interactions over the past years with this person. All of a sudden, she gets a message from this “Facebook-like” social site, which we’ll refer to as “Fakebook.” It’s her boyfriend.

In this future scenario, Fakebook has used all of their interactions together and all of his posts on Fakebook to recreate him digitally. A replicated version of him has come back from the dead based on all of the personal info the site has aggregated (now, even past posts we search for are added to the mix.) That’s an implication for the future of Facebook “getting to know us.”

There’s another episode in which everyone has a device in their ears that records everything they see, then they can replay their memories on any TV. They can fast forward and rewind through their memories and re-watch them. It starts with a guy who just had a job interview. He comes home and plays it back for the people at their dinner party, who help him analyze the looks he was getting from the interviewers to see if they think he did a good job.

The people become obsessed with reliving their memories. Could this be the end result of it becoming easier and easier to look back into the depths of our Facebooks and those of the people we care about?

It’s not just about Facebook getting to know us more and more to sell us targeted advertising. It’s personal. And if Facebook’s recent errors have proved anything, it’s that it will continue on in this direction without any deeper thought about the implications—the future affects these mechanisms will have on how we use social media in conjunction with our personal lives, with our feelings, and how these things are going to manipulate them.

When I deactivated my Facebook, it decided to tell me that one of my best friends (that passed away) would miss me. pic.twitter.com/jXKNlgjkbY

— James T. Green (@_jamestgreen) December 29, 2014